Why Survey Methodology Matters More Than Ever

Picture this: You've just launched a customer satisfaction survey expecting 1,000 responses. Instead, you get 47. Half of those are incomplete, and the other half seem to contradict everything you thought you knew about your audience. Sound familiar?

The truth is, survey research isn't just about asking questions—it's about asking the right questions, to the right people, in the right way. With response rates plummeting and survey fatigue on the rise, your methodology can make or break your research outcomes.

That's where systematic methodology analysis comes in. By examining your research design through multiple lenses—from sampling strategies to question construction—you can identify potential pitfalls before they derail your entire study.

Transform Your Research with Methodology Analysis

Discover how systematic methodology review can elevate your survey research from good to groundbreaking.

Bias Detection & Mitigation

Identify potential sources of bias in your survey design before data collection begins. Analyze question wording, response options, and sampling methods to ensure your results truly reflect your target population.

Response Rate Optimization

Analyze factors that influence participation rates including survey length, question complexity, and incentive structures. Predict and improve response rates before launching your study.

Validity & Reliability Assessment

Evaluate the psychometric properties of your survey instruments. Ensure your questions measure what they're supposed to measure and produce consistent results across different contexts.

Sampling Strategy Evaluation

Assess the appropriateness of your sampling method for your research objectives. Compare different approaches and optimize your sample size calculations for maximum statistical power.

Question Design Analysis

Evaluate question clarity, neutrality, and effectiveness. Identify leading questions, double-barreled items, and other common pitfalls that can compromise data quality.

Cross-Cultural Considerations

Analyze how cultural factors might influence survey responses. Ensure your methodology accounts for cultural differences in communication styles and response patterns.

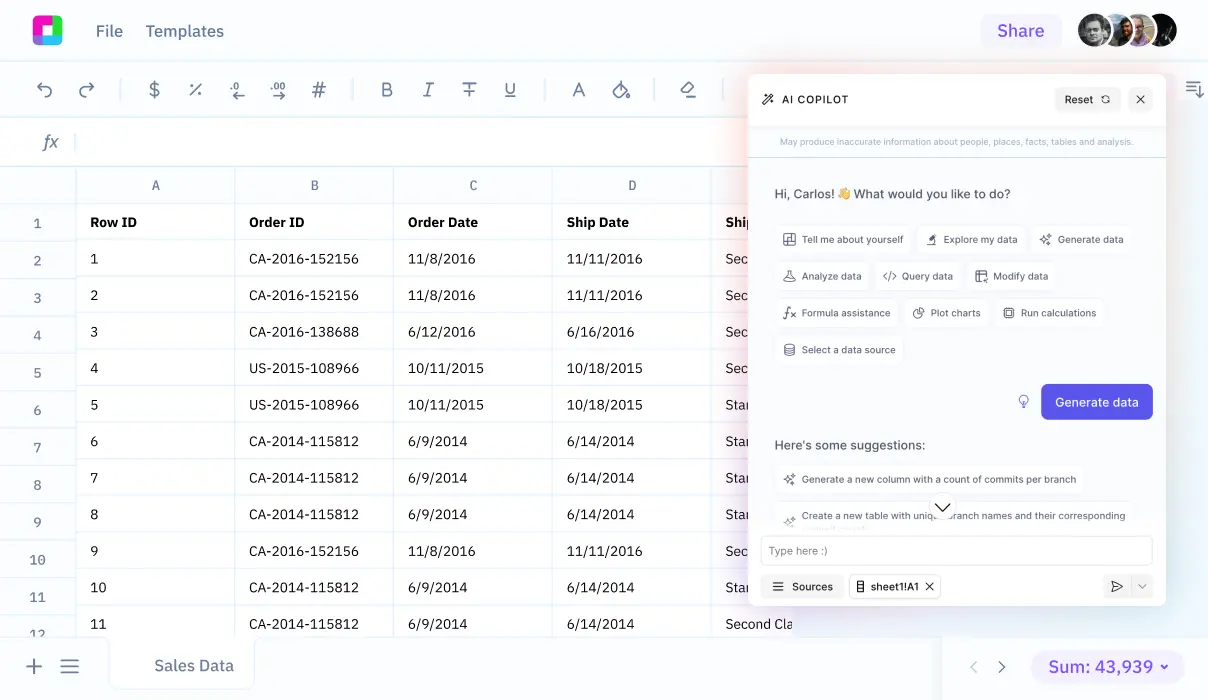

Your Methodology Analysis Workflow

Follow this systematic approach to evaluate and improve your survey research methodology.

Research Objective Assessment

Start by clearly defining your research questions and objectives. Analyze whether your proposed methodology aligns with your goals and can realistically answer your research questions within your constraints.

Survey Design Evaluation

Examine your survey structure, question types, and flow. Evaluate question clarity, response scale appropriateness, and potential sources of measurement error or bias.

Sampling Plan Analysis

Review your target population definition, sampling frame, and selection method. Calculate required sample sizes and assess potential coverage and non-response bias issues.

Data Collection Strategy Review

Evaluate your chosen data collection method (online, phone, mail, face-to-face) against your research objectives, budget constraints, and target population characteristics.

Quality Control Planning

Develop protocols for monitoring data quality during collection. Plan for handling incomplete responses, outliers, and other data quality issues that may arise.

Analysis Plan Development

Create a detailed statistical analysis plan that aligns with your research objectives and data structure. Consider power analysis, effect sizes, and appropriate statistical tests.

Survey Methodology Analysis in Action

See how different organizations leverage methodology analysis to improve their research outcomes.

Academic Research Institutions

A major university's psychology department was struggling with low response rates in their longitudinal study. Through methodology analysis, they discovered their survey was too long and contained confusing academic jargon. After redesigning with clearer language and a shorter format, their response rate increased from 23% to 67%.

Healthcare Organizations

A regional healthcare network needed to assess patient satisfaction but worried about response bias. Methodology analysis revealed that their existing survey timing (immediately after discharge) was capturing patients in a vulnerable state. By shifting to a follow-up survey one week later, they obtained more balanced and actionable feedback.

Market Research Firms

A consulting firm was seeing inconsistent results across similar studies for different clients. Methodology analysis revealed subtle differences in question wording that were creating measurement bias. Standardizing their question bank and implementing systematic bias checks improved result consistency by 40%.

Non-Profit Organizations

A community development organization wanted to measure program impact but had limited resources. Methodology analysis helped them design a cost-effective mixed-methods approach that combined a brief quantitative survey with targeted qualitative interviews, maximizing insights while staying within budget.

Government Agencies

A municipal government needed to gather citizen feedback on proposed policy changes. Methodology analysis identified potential sampling bias in their online-only approach, leading them to implement a multi-modal strategy that better represented their diverse population demographics.

Technology Companies

A software company's user experience surveys were yielding conflicting results across different product teams. Methodology analysis revealed that each team was using different rating scales and question formats. Standardizing their approach led to more reliable cross-product comparisons.

Essential Components of Survey Methodology Analysis

Question Construction Analysis

The foundation of any good survey lies in well-constructed questions. This involves examining each question for clarity, neutrality, and appropriateness. Are you asking leading questions that push respondents toward a particular answer? Do your questions contain jargon that might confuse participants? Are you asking about multiple concepts in a single question?

Consider this example: Instead of asking "How satisfied are you with our fast and reliable customer service?" (which assumes the service is both fast and reliable), a better approach would be separate questions: "How would you rate the speed of our customer service response?" and "How would you rate the reliability of our customer service?"

Response Scale Evaluation

The choice of response scale can dramatically impact your results. Should you use a 5-point or 7-point Likert scale? Is a forced-choice format appropriate, or should you include a neutral option? Different scales can lead to different patterns of responses, even when measuring the same underlying construct.

For instance, research shows that including a neutral midpoint option tends to attract about 10-20% of responses, particularly from respondents who are genuinely neutral or uncertain. Removing this option forces a choice but may introduce artificial polarization in your data.

Sampling Strategy Assessment

Your sampling approach determines who gets included in your study and, consequently, how generalizable your results will be. Are you using probability or non-probability sampling? How well does your sampling frame represent your target population? What are the potential sources of coverage error?

A common challenge in online surveys is coverage bias—certain demographic groups may be underrepresented due to differences in internet access or digital literacy. Methodology analysis helps you identify and account for these potential blind spots.

Mode Effects Analysis

The way you collect data (online, phone, mail, in-person) can influence how people respond. Online surveys might encourage more honest responses to sensitive questions due to perceived anonymity, while phone interviews might produce more socially desirable responses due to the presence of an interviewer.

Understanding these mode effects is crucial for interpreting your results correctly and for making informed decisions about data collection methods in future studies.

Avoiding Common Survey Methodology Pitfalls

The Length Trap

"We have so many important questions to ask!" It's a common refrain, but longer surveys consistently produce lower response rates and higher dropout rates. The relationship isn't linear either—going from 10 to 20 questions doesn't just double the burden; it can exponentially increase survey fatigue.

A good rule of thumb: if your survey takes more than 10 minutes to complete, you're probably asking too much. Consider whether each question is truly essential to your research objectives, or if some information could be gathered through other means.

The Timing Mistake

When you launch your survey can be just as important as how you design it. Sending a work-related survey on Friday afternoon might yield different results than sending it on Tuesday morning. Seasonal factors, current events, and organizational changes can all influence response patterns.

Methodology analysis includes considering the broader context in which your survey will be administered and how external factors might influence your results.

The Single-Method Fallacy

Relying on a single data collection method can introduce systematic bias. What if your online survey misses participants who are less tech-savvy? What if your phone survey excludes people who don't answer unknown numbers?

Consider mixed-mode approaches when appropriate, but be aware that different methods might yield different results even when measuring the same construct. This isn't necessarily a problem—it's information that can enrich your understanding of the research topic.

Advanced Survey Methodology Analysis Techniques

Cognitive Interviewing

Before launching your full survey, consider conducting cognitive interviews with a small sample of your target population. This involves asking participants to "think aloud" as they complete your survey, helping you identify confusing questions, unclear instructions, or unexpected interpretations of your items.

This technique often reveals issues that aren't apparent during expert review. For example, a question that seems perfectly clear to researchers might be interpreted completely differently by respondents from different cultural backgrounds or educational levels.

Response Pattern Analysis

Examining how people respond to your survey can reveal important methodological issues. Are participants straight-lining (giving the same response to every question)? Are there unusual patterns in completion times? Are certain questions being skipped more often than others?

These patterns can indicate problems with question design, survey length, or participant engagement. They can also help you identify potentially invalid responses that might need to be excluded from your analysis.

Measurement Invariance Testing

If you're comparing responses across different groups (e.g., different age groups, cultures, or time periods), you need to ensure that your survey questions are measuring the same construct in the same way across all groups. This is called measurement invariance.

Without measurement invariance, apparent differences between groups might reflect differences in how questions are interpreted rather than true differences in the underlying construct you're trying to measure.

Ensuring Data Quality Through Methodology Analysis

Great methodology analysis doesn't stop at survey design—it extends to monitoring and improving data quality throughout the collection process.

Real-Time Quality Monitoring

Set up systems to monitor response quality as data comes in. This might include tracking completion rates, identifying unusually fast or slow completion times, and flagging responses that show suspicious patterns.

Early detection of quality issues allows you to make mid-course corrections, whether that means clarifying confusing questions, adjusting your recruitment strategy, or implementing additional quality controls.

Non-Response Analysis

Understanding who doesn't respond to your survey is just as important as understanding who does. Non-response bias can severely limit the generalizability of your findings.

Collect basic demographic information about your sampling frame so you can compare the characteristics of respondents and non-respondents. If certain groups are systematically under-represented, you might need to adjust your recruitment strategy or apply statistical weights to your analysis.

Validation Strategies

Consider incorporating validation questions or external benchmarks to assess the accuracy of your survey responses. This might involve comparing your results to known population parameters or including questions with known answers to test respondent attention and honesty.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long should I spend on methodology analysis before launching my survey?

Plan to spend 20-30% of your total project time on methodology analysis and survey design. This upfront investment will save you time and resources later by preventing costly data collection errors and improving the quality of your results.

What's the minimum sample size I need for reliable results?

Sample size requirements depend on your research objectives, expected effect sizes, and desired statistical power. For simple descriptive statistics, 100-300 responses might suffice. For complex analyses or detecting small effects, you might need 1,000+ responses. Use power analysis to determine appropriate sample sizes for your specific research questions.

Should I use probability or non-probability sampling?

Probability sampling is preferred when you need to generalize findings to a broader population. Non-probability sampling (like convenience or snowball sampling) can be appropriate for exploratory research or when probability sampling is impractical. The key is to be transparent about your sampling method and its limitations.

How do I handle missing data in my survey responses?

First, analyze patterns of missingness—is it random or systematic? For random missing data, techniques like multiple imputation can help. For systematic patterns, you might need to adjust your analysis approach or acknowledge limitations in your interpretation. Always report your missing data strategy.

What's the best way to pretest my survey?

Use a multi-stage approach: expert review for content validity, cognitive interviews to test comprehension, and a small pilot test to identify technical issues and estimate completion time. Each stage serves different purposes and helps identify different types of problems.

How do I know if my survey questions are biased?

Look for leading language, assumptions embedded in questions, and unbalanced response options. Test questions with diverse groups to see if they're interpreted consistently. Consider having colleagues review your questions and ask yourself if someone with an opposite viewpoint would find the questions fair.

What response rate should I expect for my survey?

Response rates vary widely by survey type, population, and methodology. Online surveys typically see 20-30% response rates, while telephone surveys might achieve 10-15%. Focus on maximizing response quality rather than just quantity, and always report your response rate transparently.

How do I account for cultural differences in international surveys?

Consider translation equivalence, cultural appropriateness of questions, and different communication styles. Use back-translation to ensure accuracy, pilot test in each cultural context, and consider whether the same constructs are relevant across cultures. Sometimes you'll need culture-specific questions or analysis approaches.

Frequently Asked Questions

If your question is not covered here, you can contact our team.

Contact Us